On a misty ridge in the Eastern Himalayas, where a village might sit like a lookout ship above valleys of forest—“security” wasn’t a distant state service. It was a lived, everyday responsibility. People cultivated steep slopes, moved through thick monsoon landscapes, negotiated shifting borders of land and kinship, and built social systems that could hold a community together when the world beyond the next ridge was uncertain. This is the setting in which “warrior traditions” took shape: not as fantasies of conquest, but as community technologies—ways of organizing protection, duty, courage, and restraint.

And yes, in parts of today’s Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, and neighbouring hill belts, including some Naga groups across present-day state borders, headhunting existed historically. But if we begin and end with that word, we miss the larger story: how warfare was regulated, how violence was bounded by norms, and how these societies have long been (and remain) known for governance, artistry, textile traditions, architecture, oral history, and cultural reinvention—not for a single sensationalized practice.

In the Eastern Himalayas and the Patkai hills, geography doesn’t just shape the view—it shapes the rules of life. A ridge can be a wall. A valley can be a corridor. A monsoon can turn a “nearby” place into a day’s hard journey. So distance is felt in sweat and risk, not kilometres. In that kind of terrain, villages often become their own sturdy worlds: decision-making stays close to home, reputations matter because news travels by people, and cooperation becomes a survival skill. This is what social scientists call political ecology—the idea that forests, farms, slopes, and seasons quietly mould institutions: councils, customary laws, shared labour, and a strong sense of “we” because “we” is what works.

Once you see that, the history of conflict looks different too. In many hill societies, fighting was usually about protection—guarding land, paths, granaries, and dignity—rather than conquest for distant power. Security wasn’t something you could outsource; it had to be organized, debated, and enforced within the community. You can still spot that old reflex today, even in modern life: the way villages mobilize for road repairs, festivals, forest care, or dispute settlement; the way collective decisions still carry weight. The tools have changed—phones, schools, churches, elections—but the underlying habit often hasn’t: when something truly matters, people act together. That’s the ground on which “warrior traditions” first grew—less a love of violence, more a shared responsibility to keep the village safe and whole.

In anthropological terms, “masculinity” is a social responsibility, not masculinity as domination, and the north-east always got that!

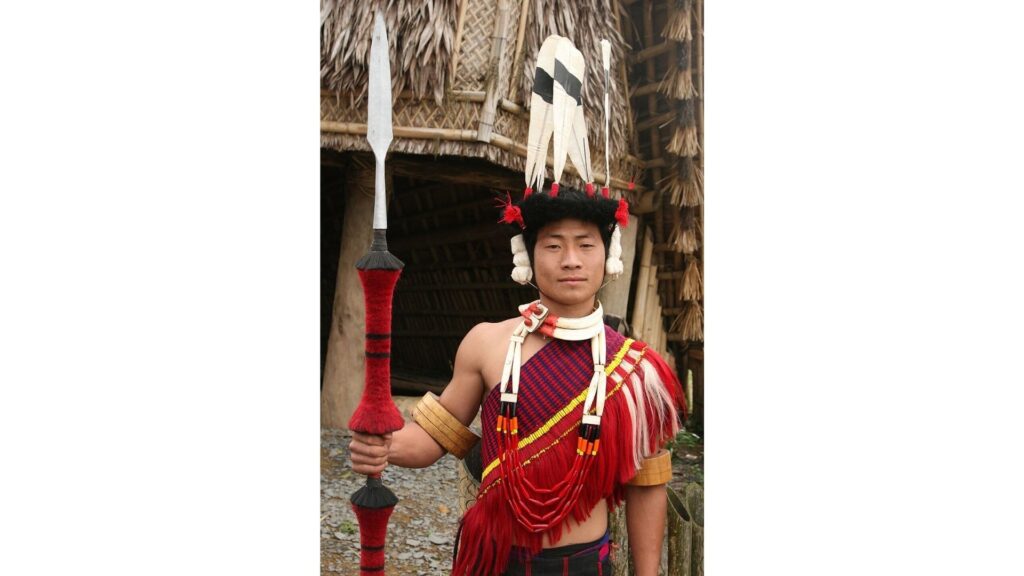

In many hill societies of the Northeast, a “warrior” wasn’t a temperament—it was a position in the village’s civic architecture. With no distant police to call and no standing army to outsource to, security lived in local institutions: councils, kin networks, reputations, and shared rules. So the warrior ideal leaned less toward “the one who attacks” and more toward “the one who can protect”—to guard fields at the settlement’s edge, watch the paths to water and trade, answer alarms, and carry the community’s dignity through disputes. Courage mattered, but it had to be disciplined: loyalty, restraint, and acting for the collective rather than for personal glory. That’s why rites of passage weren’t just about proving strength; they were transfers of trust, marking the moment a young person became accountable to the village’s moral economy—showing up for collective labour, respecting council decisions, learning skills and stories, and, when necessary, defending the community without breaking the norms that kept conflict from spilling into chaos.

In many Eastern Himalayan hill societies, conflict didn’t start with a sudden raid—it often started with conversation: in the space where elders and councils weighed a grievance, tested rumours, replayed boundary histories, and asked the hardest question first—is this worth the cost to the village? Because everyone’s lives were interlocked (fields, marriage ties, paths, water sources, reputations), violence couldn’t be left to private bravado; it had to be dragged into the village’s public institutions and made answerable to collective consent, rules, and sanctions. That impulse to “govern force” has a long afterlife: Nagaland is widely described as having layered councils (village upward) dealing with breaches of customary law, with appeals routed to the Naga Tribunal, signalling a preference for procedure over vendetta. And it’s not merely an informal tradition—India’s Constitution protects Naga customary law and the administration of civil and criminal justice involving decisions according to it (Article 371A), and Nagaland’s Village and Area Councils law explicitly recognizes village councils’ roles, including administering justice according to customary norms. In other words, even when conflict existed, it was often treated less as chaos and more as a problem of containment: set boundaries, establish accountability, prevent today’s anger from becoming tomorrow’s endless feud.

If we only translate war as “fighting,” we miss what it meant inside these societies.

Historically, headhunting in parts of the Northeast was not random violence. Ethnographic writing from the colonial period (itself politically loaded) still records how head-taking could be connected to fertility beliefs and ideas of communal prosperity—an attempt to convert danger into cosmic balance. That doesn’t make it “acceptable” in a modern moral frame—but it does make it intelligible as a ritual logic, not a horror story.

And importantly: these meanings were carried through objects and performance—shields and spears, log drums, dormitories, songs, and oral epics. In many places, the cultural memory of “war” survived most strongly in music, narrative, and art, long after the practice ended.

It’s tempting to flatten “the Northeast” into one warrior archetype, but the region is better understood as a family of neighbouring political cultures—each with its own grammar of protection, prestige, restraint, and remembrance.

The morung (and related institutions under different local names) is best understood as social infrastructure—a built space where a village “manufactured adulthood.” In many Naga contexts, it functioned as a youth dormitory and learning institution where young people were trained into community life: absorbing history and customary norms through oral teaching, learning skills and arts, practicing discipline, and internalizing duties—alongside forms of readiness tied to village defence. Sociologically, it worked like an age-grade system: it grouped youth into a public category with responsibilities, created peer accountability, and linked personal reputation to collective trust. Even the morung’s typical placement near village gates or strategic points signaled what it was for—education and protection woven into the same everyday routine.

Seen this way, the morung wasn’t just a “warrior house”—it was a civic school, ethics workshop, arts conservatory, and community watchpost rolled into one, where civics was learned by doing: labour, ceremony, story, and service. Its decline is also historically legible: as Christianity and formal education expanded in the 20th century, new institutions (churches, schools, hostels) began taking over youth socialization, reshaping moral worlds and daily schedules. Yet the morung idea persists—some communities have rebuilt or repurposed morung spaces as cultural classrooms again, using them to transmit heritage skills and collective memory in contemporary forms.

Across the early–mid 20th century, many warrior institutions (including headhunting in some communities) receded not because “time civilized the hills,” but because the political landscape shifted under people’s feet: colonial regulations tightened movement and territory, new administrative borders hardened older inter-village geographies, and missionary churches plus schools introduced new moral languages and new routes to status beyond warfare. Dolly Kikon notes how the British “civilizing” project on the Naga frontier was entangled with state interests—protecting trade and extraction—while military posts, education, and mission institutions reshaped village life from within. And crucially, colonial storytelling often froze “headhunting” into an identity label, long after communities themselves had changed; Venusa Tinyi writes that the term was essentialised as the defining identity of the Nagas during the colonial period—an imprint that later echoed in media and tourism shorthand.

What’s easy to miss is the transformation that followed: practices once tied to defence and prestige were redirected into cultural labour—festivals, performance, wood carving, weaving, oral-history work, and community-led ways of hosting visitors with dignity. The “warrior” doesn’t vanish so much as evolve into a custodian: someone who protects not by fighting, but by keeping language, craft, ritual, and memory alive—and by building institutions that make heritage economically and socially viable. Spaces like the Heirloom Naga Centre explicitly frame the present through artisan empowerment, traditional weaving, sustainable crafts, and cultural experiences—telling a story of continuity without reducing anyone to a violent past.

The phrase “last headhunters” is catchy—but it often turns living societies into a single, marketable headline (you can see it used exactly that way in popular travel writing on the Konyak). Scholars argue that this framing has a history: “headhunting” was essentialised during the colonial period as a defining identity for Nagas, and the label kept travelling long after communities had moved on. Dolly Kikon’s work also shows how the colonial “civilizing” story around “Naga headhunters” served frontier governance and economic interests, not neutral description—one reason modern storytelling needs to be careful about repeating inherited categories as if they were timeless truths. So the ethical move for writers and visitors is simple: lead with context, foreground living culture, and treat community memory as knowledge—not spectacle.

And the present-day Eastern Himalayas makes that easy because it’s not a war-zone of the past, it’s a mosaic of institutions, faith, schooling, cultural revival, and often striking community-led stewardship. Khonoma (near Kohima) is a powerful inversion of “defence”: the Village Council declared a large protected forest area, banned hunting, and notified what’s known as the Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary, shifting collective responsibility from guarding borders and granaries to guarding forests and biodiversity. That continuity—community-first governance, evolving with the times is the real story to carry home.

If we strip away the sensationalism, “warrior traditions” here offer a surprisingly contemporary lesson:

And perhaps most importantly: modern identities in the Eastern Himalayas cannot—and should not—be reduced to warfare. They are living, plural, and creatively in motion.