In Nagaland, history is not something you visit—it is something that watches you back. It lingers in forests believed to shelter ancestral spirits, in stones that once marked village frontiers, and in clan names that still remember where land was defended with blood and prayer. Here, identity is inherited through territory and memory. To be Naga is to belong to a lineage shaped by hills, spirits, and stories of survival.

The past walks beside you in these hills—etched into terraced fields, echoed in festival chants, and whispered in village councils where decisions are still guided by ancestral law. Elders speak of wars not as distant events, but as lived experience, passed down through generations like heirlooms of caution and pride. To travel through Nagaland is not merely to cross landscapes, but to step into layered worlds where the living and the ancestral coexist.

Anthropologist J. H. Hutton, writing from his years among the Nagas in the early twentieth century, observed that warfare here was never disorder—it was structure. Conflict was a way of maintaining balance: between villages, between humans and the spirit world, between honour and survival. From ritualised inter-village battles to the earth-shaking arrival of World War II, war in Nagaland did not simply destroy.

Long before colonial maps drew borders, Nagaland was a mosaic of self-governing village republics. Each village was politically autonomous, economically self-sufficient, and fiercely protective of its land. Loyalty was not abstract – it was local, lived, and defended.

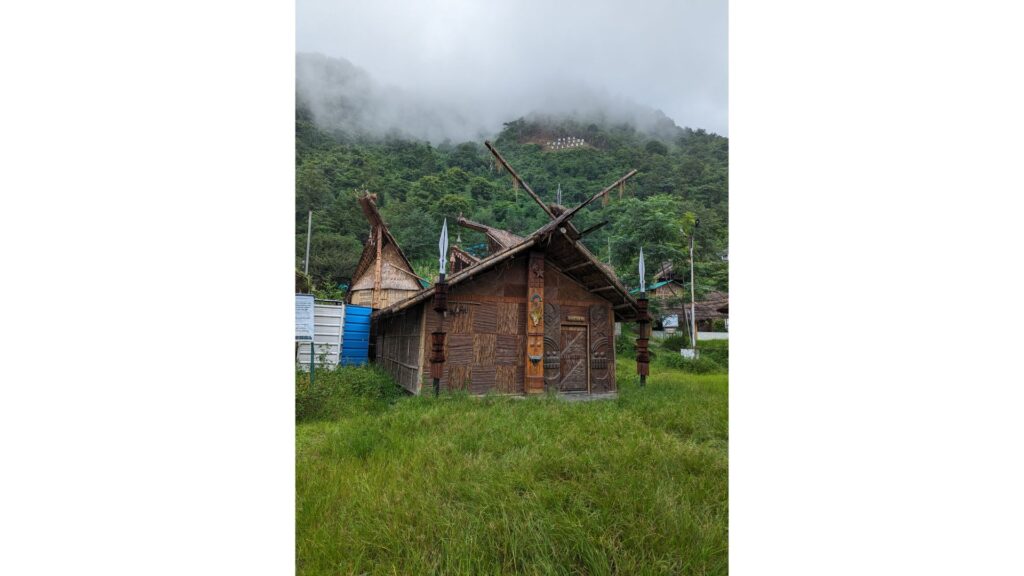

At the heart of village life stood the morung—the men’s dormitory. More than a sleeping space, it was a school of citizenship. Young boys learned oral history, woodcraft, agricultural cycles, ritual law, and, yes, warfare. As anthropologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf noted, warfare among the Nagas was “deeply embedded in social organisation rather than driven by conquest.”

Headhunting: Meaning Beyond the Myth: To outsiders, headhunting has long been sensationalised. But within Naga societies, it was symbolic rather than savage. A taken head represented fertility, protection, and communal vitality—not individual cruelty. It was regulated by strict codes: women, children, and non-combatants were off limits. Warfare functioned as a moral system—a way to maintain balance, honour, and social cohesion. Conflict was not constant, but ritualised, purposeful, and bounded.

The nineteenth century brought strangers into the hills—men in uniform, carrying maps instead of memories. To the British Empire, the Naga Hills appeared as a blank frontier to be pacified, a troublesome edge of the tea-growing plains below. To the Nagas, these intrusions were something else entirely: violations of land watched over by ancestors and protected through generations of vigilance.

British expeditions, described in colonial records as “punitive,” moved slowly uphill through forests that refused to reveal their paths. The hills turned against them. Narrow ridges became traps; supply lines thinned; silence concealed movement. Villagers, intimately familiar with every bend of the land, watched and waited.

It soon became clear that this was not a landscape that surrendered easily. Nor were its people inclined to do so. As one frustrated colonial report admitted, the Naga Hills were inhabited by “tribes who acknowledge no authority but their own”—a statement intended as complaint, yet one that unwittingly captured the core of Naga autonomy.

Khonoma, an Angami village near present-day Kohima, became the epicentre of resistance. Its warriors had long defended their land against incursions—and now turned those tactics against the British.

Guerrilla Warfare Before the Word Existed: The Angamis used trenches, stone barricades, forest cover, and night raids—strategies strikingly similar to modern guerrilla warfare. British forces laid siege, cutting off supplies, but the resistance endured for months. When Khonoma finally fell in 1880, it marked a turning point. Organised headhunting was formally ended, and colonial administration expanded.

Yet Khonoma was never remembered as a defeat.

Today, the village stands as a symbol of anti-colonial courage. As historian Julian Jacobs writes, Khonoma represents “the moment the Nagas first encountered the empire—and refused to bow easily.”

Six decades later, global war arrived in the hills.

This time carrying the weight of the world. The forests that had once hidden village warriors now echoed with the sounds of artillery and marching boots. Global conflict had found its way to one of India’s most remote frontiers.

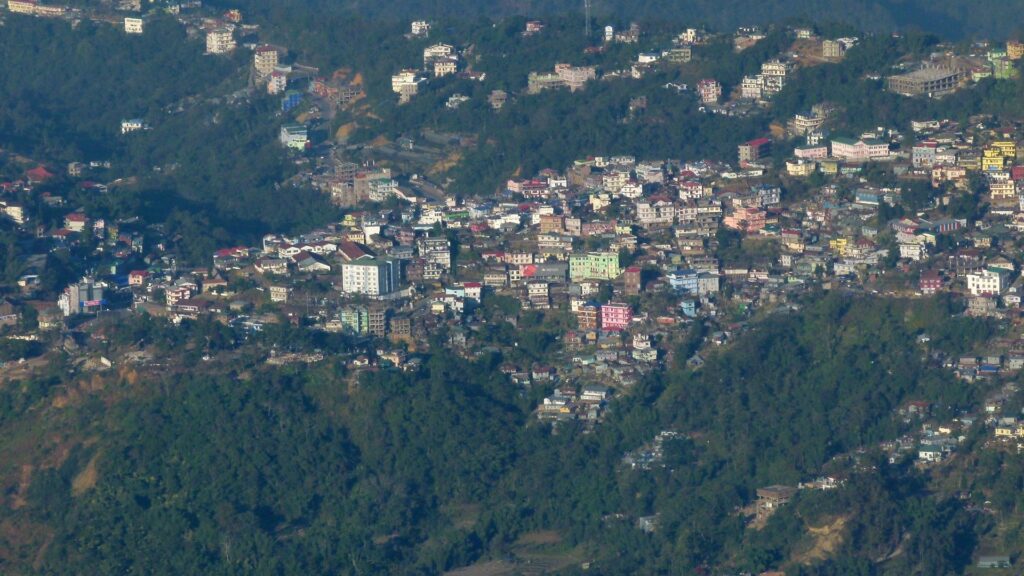

In 1944, as Japanese forces advanced through Burma, Kohima emerged as a critical threshold. Beyond it lay the plains of India; behind it, the hills that had resisted outsiders for generations. Control Kohima, military planners knew, and the road to Imphal, Dimapur, and beyond would lie open.

For Naga villagers, the war arrived without warning and without distance. Homes were occupied, granaries emptied, and terraced fields transformed into trenches. Yet the hills did not fall silent. Villagers became guides through mist and forest, carriers of supplies across impossible terrain, interpreters between worlds at war. Their knowledge of land once used for survival was now essential to strategy.

Local memories of this period are marked by contradiction—pride in contribution, but grief for what was lost. The war brought recognition, but also displacement, trauma, and stories that are still told quietly, long after the guns fell silent.

Few battles illustrate the collision of global war and local land like Kohima.

At the centre stood the Deputy Commissioner’s bungalow—and its tennis court. British and Indian troops held one side; Japanese forces dug in mere metres away. Fighting was hand-to-hand, relentless, and devastating.The siege lasted weeks. When the Allied counter-offensive finally broke through, the Japanese advance into India was halted.

Military historians later called Kohima the “Stalingrad of the East”—a turning point in the Asian theatre of WWII. Today, the Kohima War Cemetery bears the famous epitaph:

“When you go home, tell them of us and say:

For your tomorrow, we gave our today.”

In the aftermath of World War II, Naga political mobilisation took organised form with the creation of the Naga National Council (NNC) in 1946. Emerging from village councils and tribal bodies, the NNC articulated demands for self-determination rooted in customary governance. Mokokchung became a key political centre, while villages across Phek and Mon districts served as networks for mobilisation and communication, using long-established inter-village routes. Political activity remained closely tied to place, drawing legitimacy from local authority rather than distant institutions.

By the early 1950s, insurgency and military responses reshaped the region. Forested areas in Tuensang and Mon became centres of underground activity, while new administrative structures altered movement and settlement patterns. The formation of the Naga Hills–Tuensang Area in 1957 acknowledged regional complexity, leading to statehood in 1963, when Nagaland became India’s 16th state. Peace negotiations—most notably since 1997—continue to reflect histories of resistance embedded in specific districts and landscapes, underscoring how Naga politics remains grounded in land and memory.

Modern Nagaland’s struggles are quieter—but no less profound. How does one protect customary law in a globalised world? How do young Nagas balance smartphones with ancestral stories? How does autonomy coexist with nationhood?

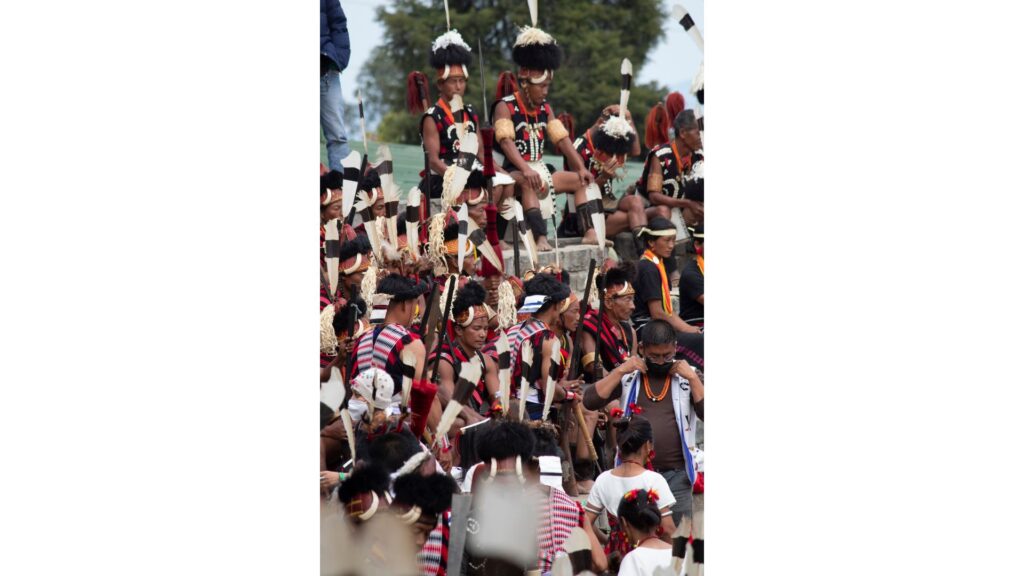

Village councils remain powerful. Festivals like Hornbill celebrate heritage not as nostalgia, but as living practice. Youth increasingly see identity as something to reinterpret, not abandon.

As one young scholar from Kohima put it: “Our history is not behind us. It is something we carry forward—carefully.”

Nagaland is not defined by conflict—but by resilience shaped through conflict.

Its history offers lessons in community strength, negotiated modernity, and the costs of misunderstanding cultural worlds. For travellers, this past provides essential context. To walk these hills without knowing their stories is to miss their meaning. To understand Nagaland’s battles—ancient and modern—is to understand why pride, autonomy, and memory matter so deeply here.

And perhaps, to travel more thoughtfully everywhere else.