In Nagaland, food begins long before it reaches the plate. It begins in forest paths and jhum fields, in rivers and home gardens, in smoke rising from hearths and hands working patiently through seasons. What is eaten here carries stories of land and labour, of climate and community, of relationships built and maintained over shared meals. To speak of Naga food without speaking of culture is to hear only the sound, not the meaning.

Yet much of the outside conversation has approached this food through a narrow lens—searching for novelty, shock, or spectacle. These framings strip everyday practices of their context, turning complex food systems into curiosities and overlooking the deep ecological knowledge, social organisation, and historical realities that shape how people eat.

Food is never neutral. In Nagaland, it is both personal and political—reflecting how communities adapt to terrain, share resources, and sustain identity across generations. Understanding Naga food therefore requires more than curiosity. It asks for attentiveness, humility, and care.

Nagaland is not a single cultural landscape but a mosaic of peoples. Home to more than a dozen major tribes and numerous sub-tribes, the region is shaped by linguistic diversity, distinct social systems, and highly localised food traditions. Food here functions as a marker of identity—signalling tribe, geography, and season. What is eaten in a Konyak village near the Myanmar border may differ significantly from what is cooked in an Angami household near Kohima, shaped by variations in altitude, forest cover, rivers, farming practices, and historical patterns of contact and movement.

For this reason, there is no single “Naga cuisine.” Angami, Ao, Sumi, Lotha, Chakhesang, and Konyak food practices differ not only in ingredients, but in methods of preparation, preservation, and the cultural meanings attached to meals. Even neighbouring villages may follow distinct culinary rhythms, shaped by micro-ecologies and inherited knowledge. This diversity resists easy categorisation, and attempts to compress Naga food into a singular narrative risk erasing the plural realities that define Naga life itself.

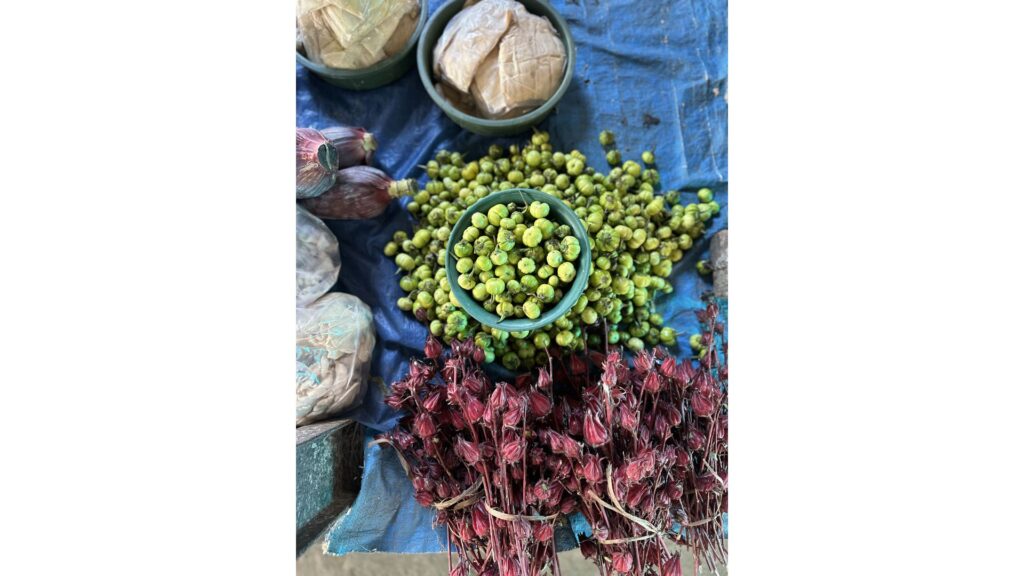

Ingredients come from many sources: wild-foraged greens and herbs gathered from forest edges, fish from streams and rivers, crops grown through shifting cultivation, and vegetables grown close to the home. Many everyday dishes feature leaves, shoots, and plants that may be unfamiliar to visitors but are deeply seasonal and locally understood, reflecting generations of ecological knowledge rather than written recipes.

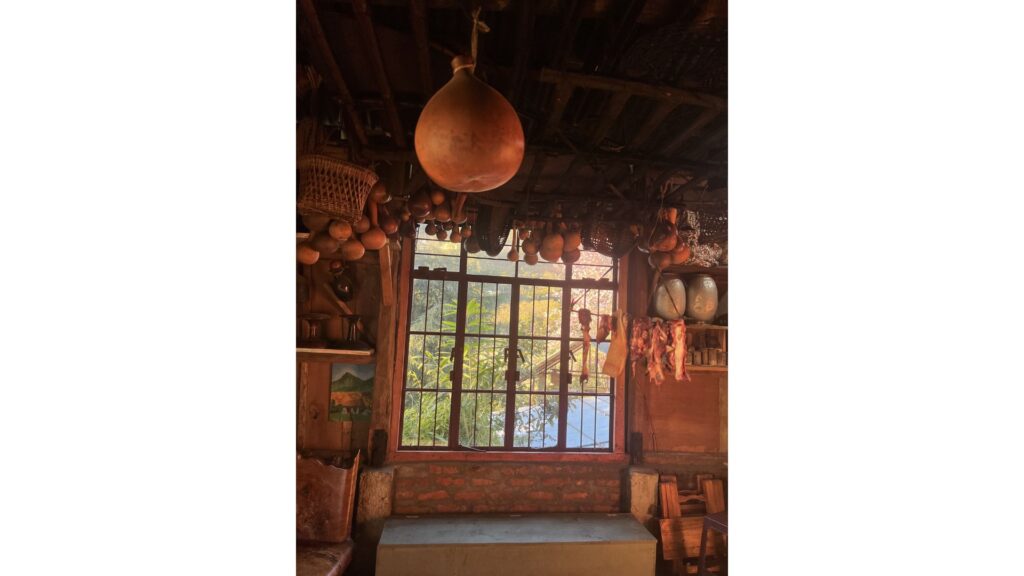

Jhum fields provide staples such as rice, millets, maize, tubers, and beans, while home gardens supply chillies, pumpkins, gourds, leafy greens, and medicinal plants used both for flavour and healing. What appears on the plate changes with monsoon rains, harvest cycles, and forest availability—fresh bamboo shoots during the rainy season, smoked and dried foods in colder or leaner months.

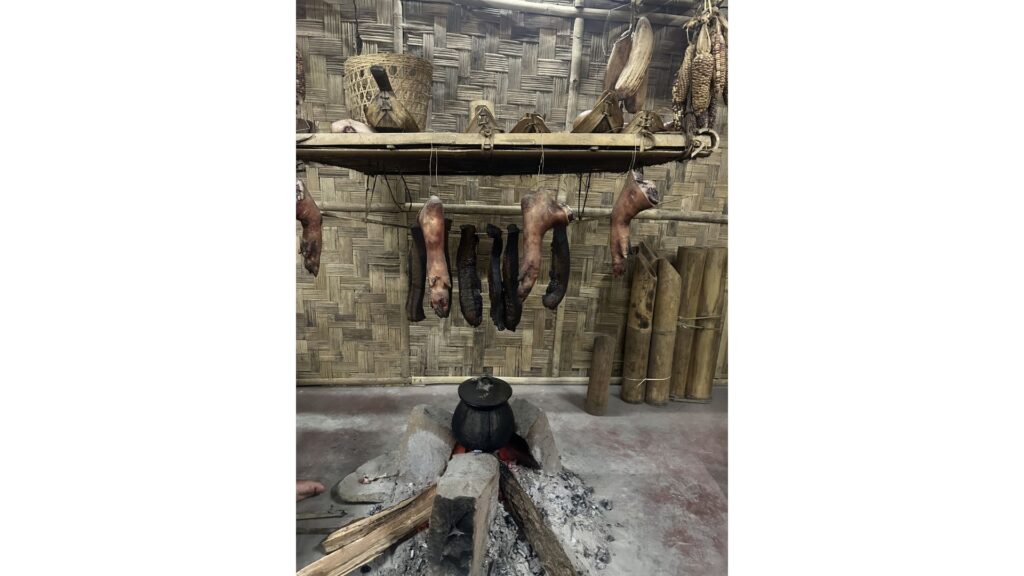

Preservation techniques in Nagaland evolved as practical responses to long monsoons, difficult terrain, and periods of limited access to fresh food. Smoking, drying, and fermentation allow food to be stored, transported, and shared across seasons. Smoked meats and fish are common, not as indulgence but as sustenance. Fermented bamboo shoot, soybeans, and fish carry strong flavours that are culturally familiar and nutritionally significant. These processes are not merely about taste—they are about survival, continuity, and skill passed down through generations. In many households, the act of fermenting or smoking food is communal labour, embedded with cultural knowledge and social cooperation.

Meat in Naga food cultures is best understood within the context of agrarian and foraging livelihoods rather than through modern ideas of abundance or choice. Traditionally, meat consumption was seasonal and closely tied to agricultural cycles, community festivals, rituals, or successful hunts. It was not an everyday indulgence but part of collective moments—marking celebration, gratitude, or transition within village life.

Importantly, meat was shared, not individualised. Animals were distributed within the community, reinforcing social ties, reciprocity, and shared responsibility for resources. Meals centred on participation rather than preference, with food functioning as a social bond rather than a personal statement.

A common misconception is that Naga food revolves solely around meat. In reality, rice is the central staple, accompanied by a wide variety of vegetables, greens, tubers, legumes, and fermented plant-based foods.

Busting myths regarding vegetarianism now! Vegetarian dishes are abundant and often simple—boiled, steamed, lightly sautéed—allowing the natural flavours of ingredients to stand out. Unlike many other Indian cuisines, flavour here comes less from heavy spice blends and more from freshness, fermentation, smoke, and texture. For many households, everyday meals are plant-forward, shaped by availability rather than ideology.

Food from Nagaland does not circulate in a political vacuum. It enters public discourse shaped by long histories of colonial classification, frontier governance, and the persistent marginalisation of Indigenous cultures from India’s mainstream imagination. During the colonial period, Naga societies were often represented as “primitive” or “other,” a framing that justified territorial control while dismissing complex systems of land use, governance, and ecological knowledge. Contemporary portrayals of Naga food as exotic or shocking echo these older hierarchies, reproducing a gaze that treats difference as spectacle rather than as lived reality.

Anthropologically, food narratives reveal how power operates through representation. Who has the authority to label certain foods as acceptable, transgressive, or sensational is closely tied to histories of land dispossession, militarisation, and political invisibility in the region. When Naga meals are reduced to viral content, the deeper contexts of subsistence economies, community sharing, and cultural resilience are erased—along with ongoing struggles over land, autonomy, and identity. To write about food from Nagaland with care is therefore a political act: it challenges inherited stereotypes and insists that everyday practices be understood on their own terms, not filtered through sensational or extractive storytelling.

For travellers, food in Nagaland can be a powerful doorway into deeper cultural understanding—if approached with responsibility and humility. Choosing local eateries, women-run kitchens, and community-based food experiences helps ensure that tourism supports local livelihoods rather than extracting value from them. When meals take place in private homes, respect for household boundaries is essential: asking questions politely, accepting what is offered without entitlement, and paying fairly for home-cooked food are small but meaningful acts of reciprocity. Responsible food tourism is not about access at all costs, but about consent, respect, and mutual exchange.

Ultimately, food in Nagaland is a living archive—of land and labour, memory and identity. To eat here is not simply to encounter something unfamiliar, but to step into ways of life shaped by environment, history, and collective resilience. Respect matters more than curiosity, and understanding matters more than reaction. For those willing to observe, listen, and learn before judging, food becomes more than what is on the plate—it becomes a lesson in how cultures endure, adapt, and continue to nourish their communities.