“A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit.” - Greek Proverb

Table of Contents

The Origins

The Process

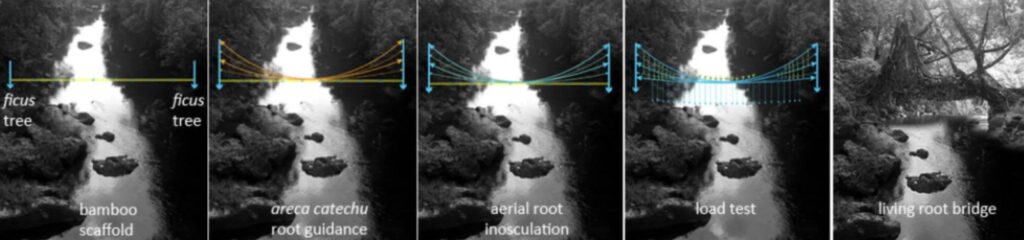

The process of creating living root bridges is a complex and intricate one that combines the skills of the local people with the natural growth patterns of the Ficus elastica tree. The process begins with selecting a suitable tree on one side of the river or stream, typically one that is at least a decade old. The young roots are placed in hollowed Areca catechu trunk for nutrition and environmental protection. The tree’s aerial roots are then guided and trained to grow across the water, using techniques such as bending, tying, and weaving.

The roots of the Ficus elastica tree are naturally inclined to grow towards a source of moisture, and when they come into contact with the water, they begin to thicken and strengthen. As the roots grow, the villagers continue to guide and shape them, weaving them together to form a strong and stable bridge. Temporary structure made of wood or bamboo is placed on the bridge and over time, the roots fuse by anastomosis to form a strong bridge that can take take loads. Periodic replacment of bamboo takes place as the roots grow in thickness and strength.

The Ficus elastica tree is well suited for this purpose, as it has a strong and flexible root system that can withstand the forces of flowing water and heavy loads. Additionally, the

tree’s aerial roots are capable of absorbing oxygen from the air, which allows them to continue to grow even when submerged in water. Due to the Ficus elastica tree’s ability to anchor itself to steep slopes and rocky surfaces, it’s easy to encourage the roots to take hold on the opposite sides of river banks.

The process of creating these bridges can take anywhere from 15 to 30 years, depending on the width of the waterway and the skill of the villagers. During this time, the bridge is continuously maintained and strengthened by the local community

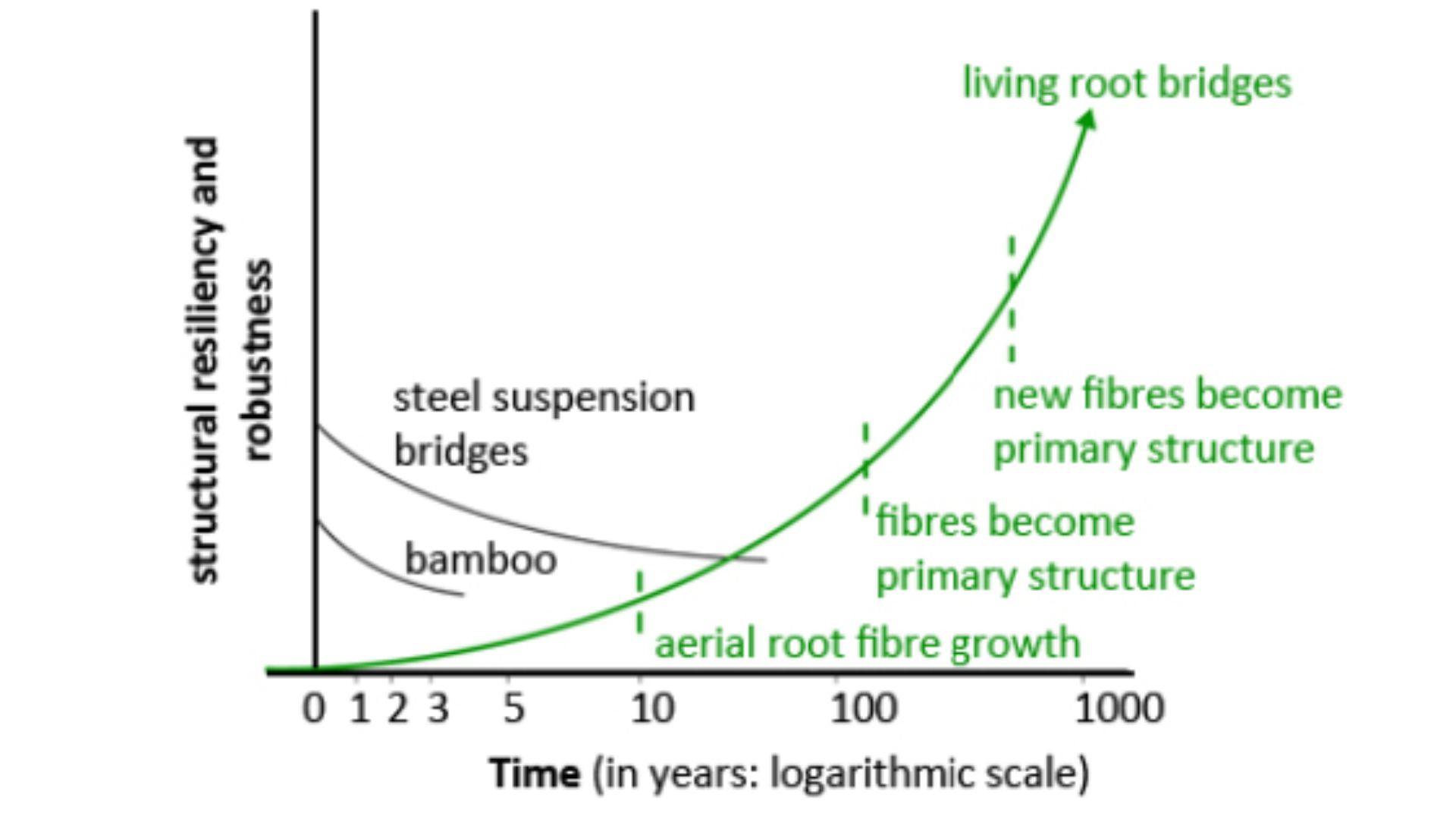

The resulting structure is a living and self-sustaining bridge that does not require the use of any non-biodegradable materials and has minimal environmental impact. The root system of the tree also helps to strengthen the surrounding soil and prevent erosion. Once the bridge is fully formed, it can last for several decades, with some reported to have a lifespan of over a century.

These root bridges are over a hundred feet long and would take 10 to 15 years to become functional. Because they’re made of living, growing organisms, living root bridges have a variable lifespan. Root bridges can last for hundreds of years under ideal conditions. The bridge will naturally self-renew and self-strengthen as long as it comes from a healthy tree

What makes the living root bridges so unique globally?

Living root bridges are an exceptional example of vernacular architecture that uses the manipulation of tree growth as a building technique, known as the “Baubotanik” approach in architecture. These bridges were created without using modern design tools and connect homes, fields, villages, and markets by spanning across canyons and rivers.

They offer an alternative to conventional technologies and materials and are particularly well-suited to the geography and climate of Meghalaya, which is characterized by high humidity, heavy rains, rapidly flowing rivers, and steep, densely forested hillsides.

The creation of living root bridges is a slow process that can take several decades to complete. The maintenance of these bridges is a combination of human intervention and natural growth, allowing them to last for centuries and grow stronger over time. The fact that the creators of these bridges may not even get to see the finished product in their lifetime is a testament to the foresight and long-term thinking that goes into this unique form of architectural production.

Living root bridges are not only functional structures, but they are also intrinsically connected to their surroundings. They provide slope stability and contribute to the ecosystem in various ways. They produce their own building material on site and absorb CO2 over their entire lifespan, making them an example of regenerative design and development that goes beyond the traditional concept of sustainable design, which aims to meet current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same. They are an outstanding example of regenerative design and development.

Well-known Root Bridges of Meghalaya

There are more than a hundred living root bridges in Meghalaya. Below are just a few examples, and there are many other living root bridges in Meghalaya that are worth visiting. However, it’s worth noting that the exact length and age of these bridges can vary depending on the source, and this information is not always accurately recorded

Umshiang or the Double Decker Living Root Bridge in Nongriat

About 30 metres long, the Double-decker root bridge is nestled amidst the village of

Nongriat. Situated 2400 feet down the valley and a climb down of approxiately 3500

stairs, this trek to Nongriat might leave your knees trembling.

The trek starts from Tyrna, a village about 13 km away from Sohra (Cherrapunjee)

It is believed that this living root bridge is over 250 years old. According to local sources, there was once a single root bridge engineered over the Umshiang river. However, due to heavy rains in the monsoon season that led to the overflow of the river, the bridge was often left submerged. This resulted in the building of an upper bridge, giving rise to one of the most remarkable natural wonders in the world – the double-decker living root bridge.

Upon reaching Nongriat, one can trek for another hour to get to the most famous gem of

Meghalaya – Rainbow Falls, a natural pool with crystal clear water.

Single-level living root bridge in Riwai - Mawlynnong

RIVER: Umshiang River

AGE: 250+ years

DISTANCE: 75 ft

A popular destination that puts Meghalaya in the larger picture is the Single-level root bridge located in the Riwai Village, 80 km (approx) away from the capital city of Meghalaya.

A 300-metre hike into the Riwai Village rainforest to the natural bridge. The hike is comparatively easy. This living root bridge is a bit thicker and wider than the doubledecker root bridge. There’s a stream running underneath it, surrounded by lush greenery. This is a convenient option for people who don’t want to hike the doubledecker root bridge.

Rangthylliang

Preservation and Conservation of the Bridges

Preserving and conserving the living root bridges of Meghalaya requires a multifaceted approach that involves the local community, promotion of sustainable tourism, environmental protection, research and monitoring, preservation of traditional knowledge, and government support.

Programmes have been conducted in relation with the rejuvenation of living root bridge under RUSA Equity Initiative Scheme 2019-20 on the theme, Learning about Traditional Innovative Ideas and Conservation of Living Root Bridge.

How can we contribute as conscious travellers?

- Please pick up your own waste! Most of the living root bridges are accessible after long hikes and treks into the dense forest covers of Meghalaya. Please ensure that you do not litter and pick up any non-degradable waste you see on the way! Every bit makes a difference.

- Connect with the local council or community in charge of taking care of the living root bridge you are visiting. Oftentimes, the guardians remain invisible while the front faces of tourism make most financial profits. Know that there is a community the size of villages that preserve and protect each living root bridge.

- Do not climb the trunks and roots of the bridge that do not make up the pathway

- In the name of ‘offbeat’ or ‘lesser known’ root bridges, please make sure that the root bridge that you are visiting is not in its early life stage – these bridges often do not have structural safety during the intial growth stages and it is important to let them perpetuate in its own pace without us getting in its way.

Conclusion

Sources

Living Systems: Designing Growth in Baubotanik. 2012 (Ferdinand Ludwig, Hannes Schwertfreger & Oliver Storz)

Living Root Bridges: State of knowledge, fundamental research and future application. (Sanjeev Shankar)

Team ChaloHoppo

Anali Baruah writes on culture and tourism in north eastern regions of India. She is currently doing her PhD in Cultural Studies and works with Content & Research at ChaloHoppo.

Our Set Departures to Meghalaya

Our Short Escapes to the Living Root Bridges

You may also like to read: