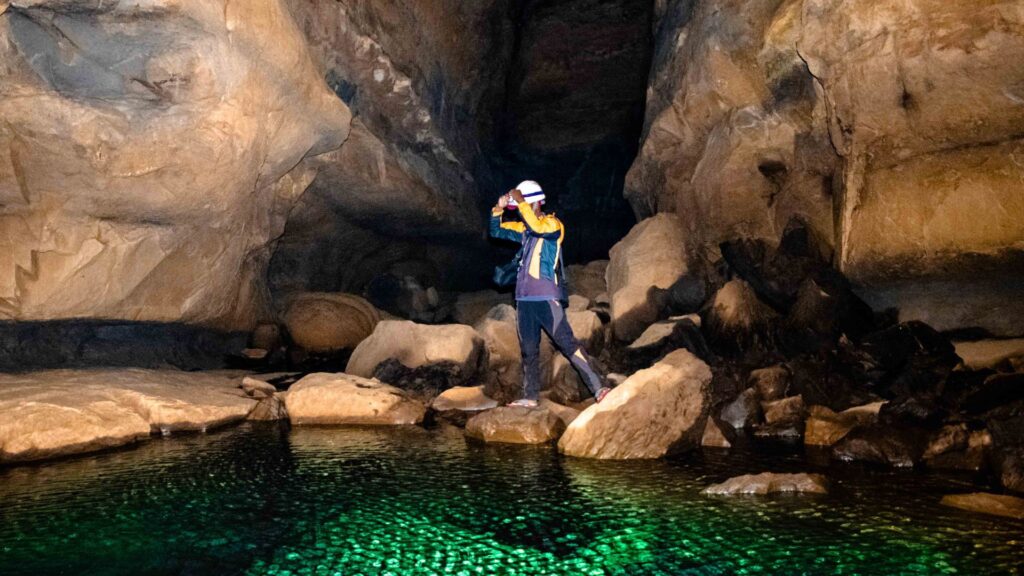

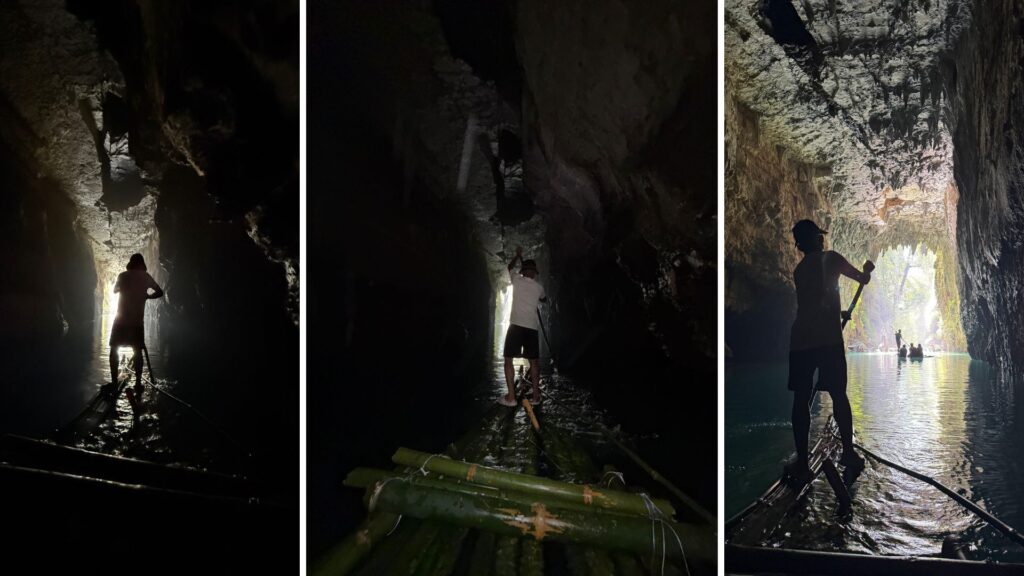

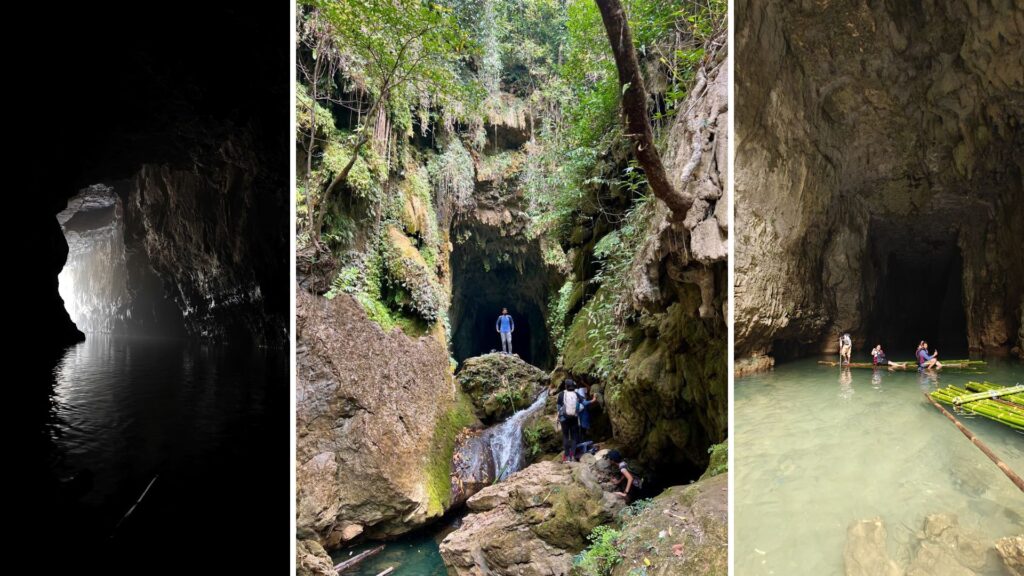

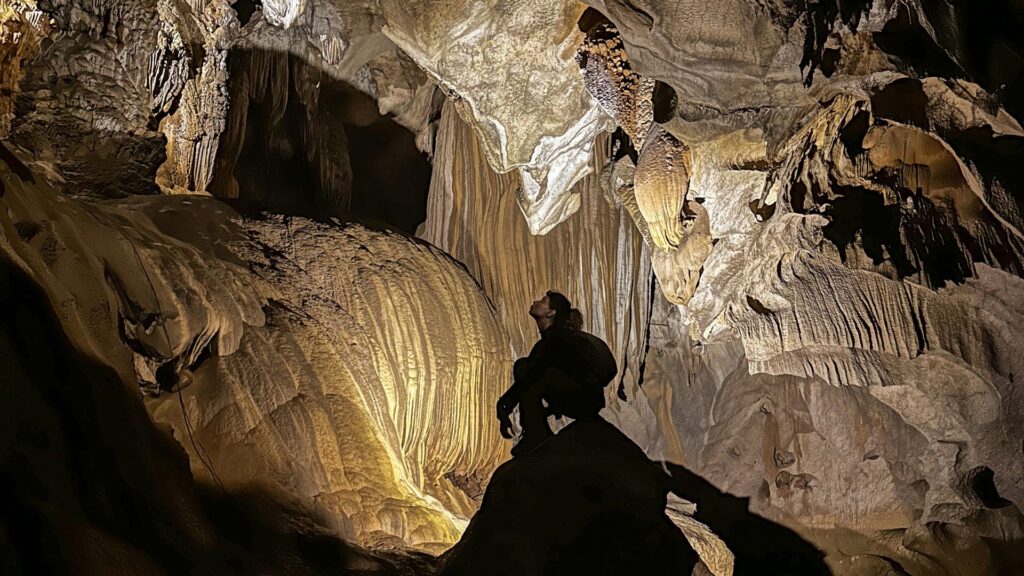

Torchlight trembles across ancient limestone as an underground stream roars somewhere in the dark. Welcome to Underground Meghalaya, where cave systems—not single caves but vast, interconnected webs of tunnels, chambers, sinkholes, and sleeping rivers, lie hidden beneath the Khasi, Jaintia and Garo Hills. Together, they form one of the longest and deepest subterranean frontiers in Asia, stretching for hundreds of kilometres beneath the misty surface of the “Abode of Clouds”.

This blog takes you into that world—where geology meets anthropology, folklore meets colonial intrigue, and adventure is written not in guidebooks, but in stone.

Meghalaya is home to over 1,700 explored caves, nine of India’s ten longest, including Krem Liat Prah (30.9 km) — a giant limestone system with a chamber so massive it’s named the Aircraft Hangar. Krem Puri (24.5 km), the world’s longest sandstone cave, and Krem Mawmluh (7.2 km) also dominate this subterranean landscape. Yet explorers believe only 5% of the underground network has been mapped! In 2025 alone, a single international expedition added over 22 km of new passages, pushing the known systems well beyond 573 km. Formed by relentless monsoon rainfall dissolving softer limestone over millions of years, these caves aren’t static — they grow, collapse, connect, and continue to surprise even seasoned cavers with hidden junctions and river passages.

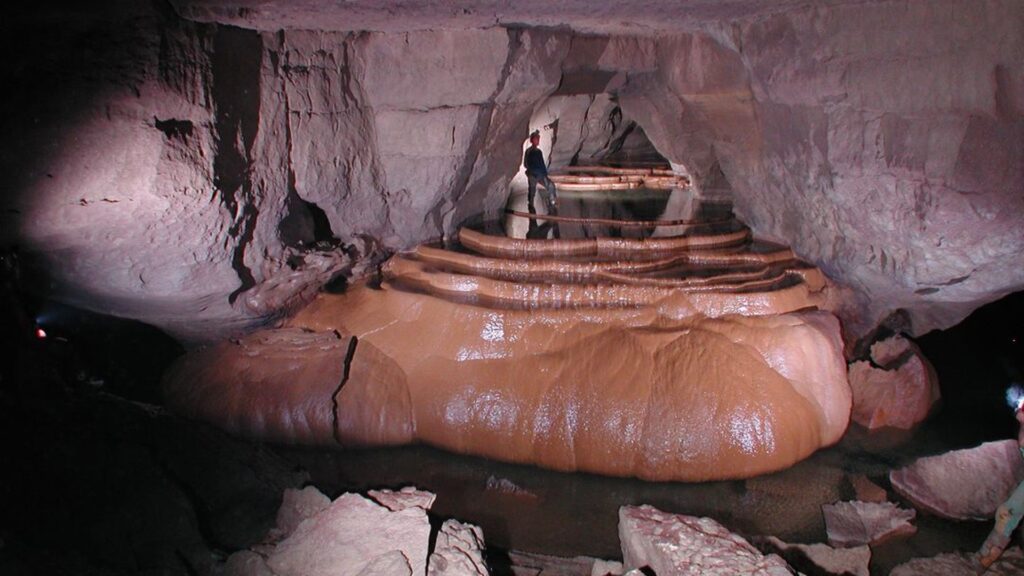

At the heart of this region is Krem Mawmluh, the site selected by global geologists as the official “golden spike” — a precise reference point on Earth’s timeline used to declare the beginning of the Meghalayan Age, the newest stage of the Holocene epoch. Inside this cave, millennia of slow water-drip have built towering stalagmites and flowstones, comprising layered mineral deposits rich in calcium carbonate, silica, iron oxides, and trace elements like magnesium and uranium.

Much like tree rings, these banded formations preserve microscopic chemical clues about past rainfall, temperature, and even desert dust. Around 4,200 years ago, one layer suddenly reveals a dramatic rise in oxygen-18 isotopes — a telltale marker of severe drought — corresponding with a catastrophic arid event that helped topple civilisations from Egypt’s Old Kingdom to Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. It is this single line, embedded within a stalagmite in Krem Mawmluh, that scientists used to formally define the start of the Meghalayan Age.

In 2022, the cave was honoured by the UNESCO-backed International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) as one of the world’s Top 100 Geological Heritage Sites, transforming Meghalaya’s dark, dripping interiors into a global scientific benchmark that literally anchors a chapter of Earth’s history.

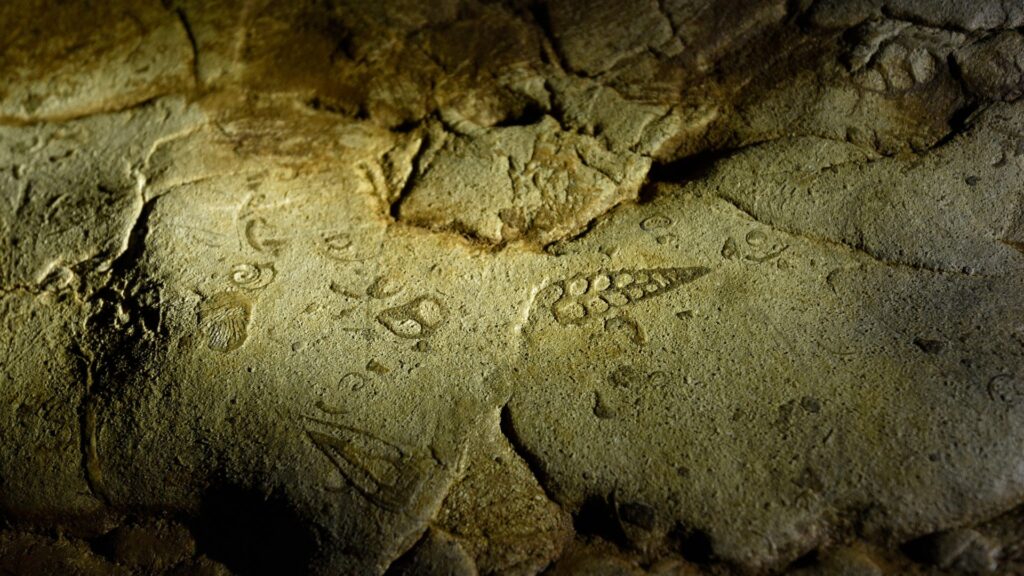

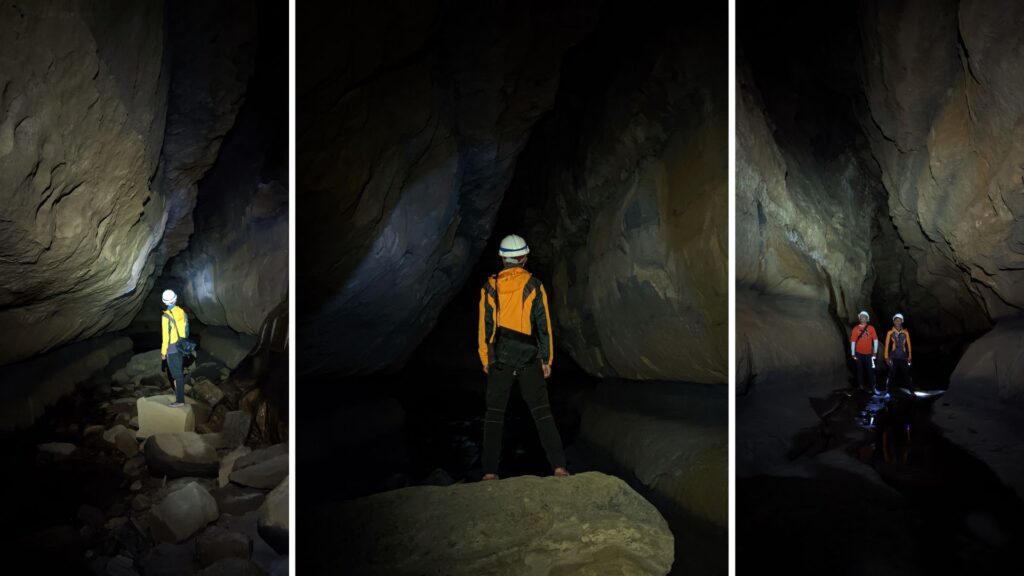

The British were the first outsiders to document these mysterious caves, starting with Lt. Yule in 1844. By the early 20th century, anthropologists and naturalists were mapping Siju Cave (nicknamed The Bat Cave) and cataloguing its blind fish and fluttering bat colonies. Post-Independence, the torch passed to the Meghalaya Adventurers Association (MAA) in 1994. Their “Caving in the Abode of Clouds” expeditions, featuring cavers from Europe, India, and the armed forces—have today become legendary, uncovering everything from dinosaur fossils in Krem Puri (the world’s longest sandstone cave) to pristine river passages in Krem Synrang Pamiang.

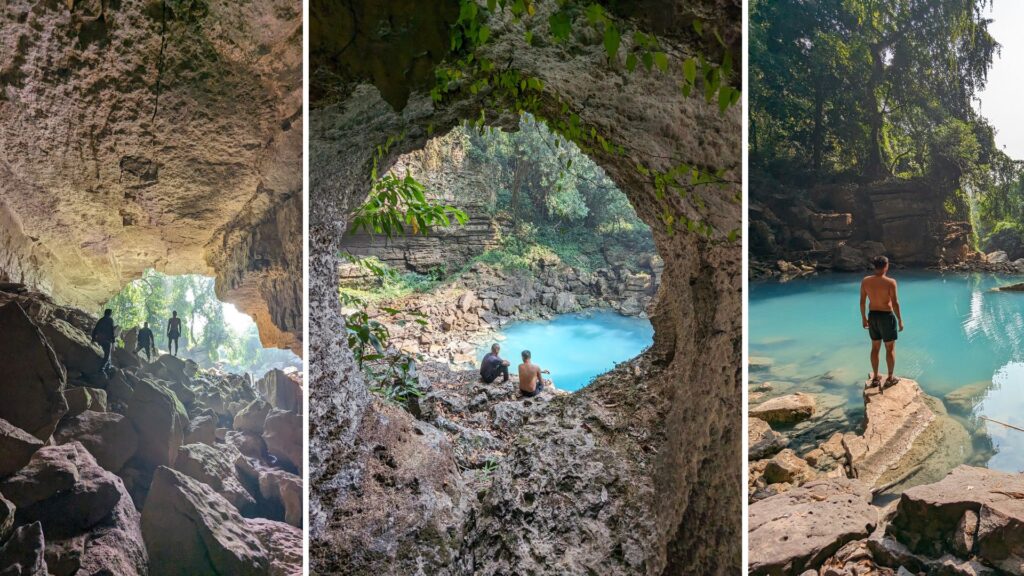

Locally, caves (Krem in Khasi) are more than voids — they’re woven into folk stories of spirit worlds. Scientifically, each functions as an ecological time capsule. Krem Synrang Pamiang shelters the endangered blind fish Schistura papulifera; Siju Cave hosts unique arachnids and enormous bat colonies; while Arwah Cave (300 m) contains fossil-bearing limestone walls believed to be over 30–40 million years old. Yet these fragile systems face threats from limestone mining, quarrying, and construction — sparking ongoing battles between conservationists and industry.

Today, Meghalaya is rightly termed India’s “Caving Capital.” With over 1,700 caves explored, tourists can traverse caverns, subterranean streams, fossils, and ancestral rocks—all shaped by relentless limestone erosion and torrential rainfall.

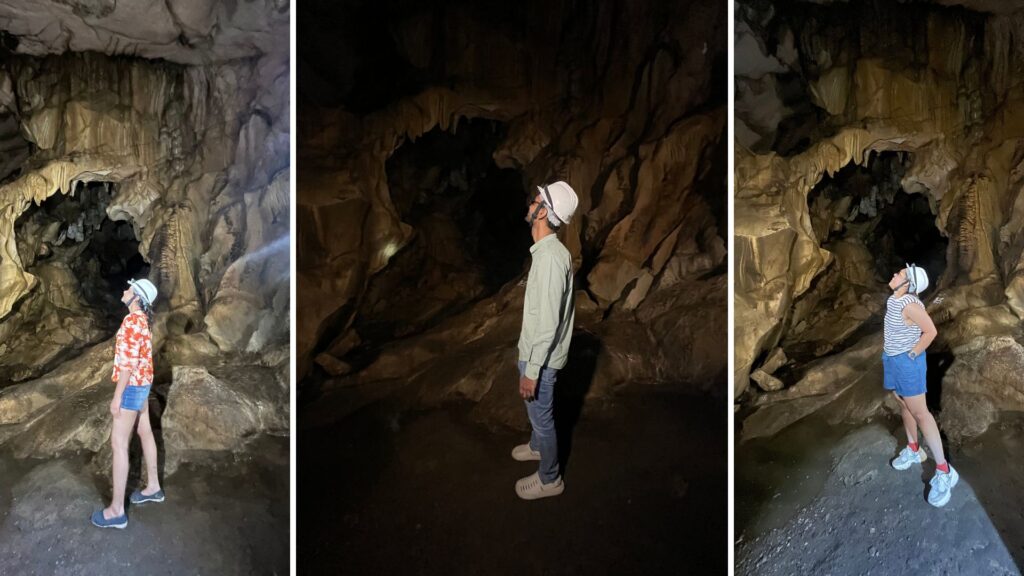

Whether you dream of easy walkways or raw speleological thrills, Meghalaya earns its title as India’s “Caving Capital”. With accessible limestone corridors, underground rivers, and immense karst formations, there’s a cave for every kind of traveller.

Best time to visit? November through March offers dry, safe conditions. During monsoons, caves can flood instantly — turning corridors into roaring drains.

How to visit: Book your caving experience through ChaloHoppo (active in Sohra/Cherrapunji and Shillong), pack lightweight layers, and be ready to get wet.

Guides — who are mandatory for all serious cave entries — provide helmets, lamps and ropes, and know how to navigate the ever-shifting passages safely.

Proper kit matters: carry a headlamp with backup batteries, wear non-slip rubber-soled boots for grip on slick limestone, and choose quick-dry clothing, as it gets humid, and often surprisingly muddy, deep underground.

Cave | Length (km) | Experience | Best For |

Mawsmai (Sohra) | 0.15 km | Short, lit, sculpted karst corridors | Families & first-timers |

Arwah | 0.30 km | Fossil-rich limestone walls | Culture & photo enthusiasts |

Krem Lymput | 6.5 km | Hidden river passages, vertical squeezes | Adventure-inclined explorers |

Krem Mawmluh | 7.2 km | Knee-deep streams, ropework sections | Soft-core thrill seekers |

Krem Liat Prah | 30.9 km | Endless passages & massive chambers | Serious caving aficionados |

Krem Puri | 24.5 km | Maze-like sandstone tunnels | Fossil & geology buffs |

Siju Cave | 4.77 km | Bat swarms + underground river | Wildlife & thrill fans |

Equal parts policy wonk and wanderlust junkie, Kavya brings together her training in environmental economics and political science with an enduring curiosity about how the world works — and how it could work better. By day, she’s a public health researcher and advocate, working at the intersection of people, systems, and the planet.

Off the clock? She’s a storyteller, active rester, and cat mama.