Morning in Ziro doesn’t begin; it unfurls. The valley exhales a thin breath of mist that drifts over pine ridges and settles on rice terraces like a secret being kept by the hills. It braids itself through pine ridges and rice terraces that glow like wet jade, while egrets lift from paddies where carp ripple the mirrored sky. By first light, the valley’s quiet genius shows: bamboo channels guiding mountain water into step-cut fields, hearths coaxed awake, a gourd rinsed at the threshold, smoke threading the air with pork and pine. Ziro’s place on UNESCO’s tentative list isn’t for stone, but for a softer architecture — human hands, living soil, attentive water — that has kept rice and fish in covenant for generations.

Amid this living landscape dwell the Apatani, moving to a rhythm as patient as gravity. Councils gather on wooden lapang to settle the day’s work; nyibus murmur origin lines that bind ridge to river, people to place. Women tend the hearth that warms both millet and memory; men plane bamboo to the grain’s insistence. Festivals arrive like duty performed with joy, and modernity like a courteous guest — a solar panel on thatch, a phone buzzing beside a woven basket — careful not to speak louder than the valley itself.

The Apatanis are one branch of the wider Tani constellation—Adi, Galo, Nyishi, Tagin, Mising, and others—spread across Arunachal’s river valleys and ridgelines. Their mother tongue, often called Tanii / Tanw Aguñ, sits within the Sino-Tibetan family; linguists even flag it as an “early-branching” Western Tani language with some divergent features, which helps explain why so much memory here travels by voice and drum rather than by script. Until colonial forays in the early 20th century, Ziro’s plateaus were largely self-contained; British records mention expeditions meeting organized resistance, a reminder that isolation was as much political choice as geography.

What holds village life together is an everyday constitution you won’t find in a book. The Bulyang—the village council—presides in the open, mediating disputes, levying fines, and steering collective work; UNESCO’s tentative-listing note for the “Apatani Cultural Landscape” even highlights how these councils govern by appealing to conscience rather than fear, privileging prevention over punishment. Recent headlines about fringe “Taniland” militancy elsewhere in Arunachal underline how pan-Tani identity can surface in modern politics, but in Ziro the durable news is quieter: customary councils, elastic law, and consensus as civic habit.

Imagine paddies where fish dart among the stems — not by accident, but design. The Apatani rice–fish ecosystem is a marvel of indigenous engineering: no machinery, no fertilizers, just bamboo channels guiding mountain water into fields that shimmer with life. Each terrace is privately owned yet tended in collective spirit — an economy of trust. Their methods, passed down over centuries, have drawn UNESCO recognition as models of sustainable farming. During the Dree Festival, the valley celebrates this ecological symphony, offering prayers to keep pests, drought, and discord away.

Fun fact: Apatani farmers have maintained consistent rice yields without soil depletion for generations — something modern agronomists still struggle to replicate.

Walk into Hong or Hija and the architecture reads like a field note in timber and reed: houses lifted on pine posts with bamboo floors and walls, steep thatch pitched to shed mountain rain, smoke drifting from low eaves where meat is cured above a central hearth. Structural pine provides the frame while bamboo (notably Phyllostachys/Phyllostachys bambusoides in local studies) skins the envelope; farmers even reuse pine needles as mulch—an ecologically tight loop that mirrors Apatani agriculture. These are not museum pieces but living vernacular—resilient to damp, quick to repair, and entirely sourced from the valley.

Village space is choreographed around the lapang, an open wooden platform where elders deliberate, disputes are settled, and visitors on heritage walks during the Ziro Festival are introduced to Apatani law and origin lore; the domestic hearth, meanwhile, anchors kinship and everyday labor inside. This civic–domestic pairing—lapang outside, fire inside—keeps decision-making public and hospitality intimate, a pattern noted in UNESCO’s “Apatani Cultural Landscape” brief and showcased in community-led tours that have themselves become part of the valley’s contemporary story

If you ever want to see time bend, visit during Myoko in March. Friendships are renewed with ritual wine and chants that feel older than language. By January, Murung brings a wave of prosperity — feasts, mithun sacrifices, and nights of storytelling under a thousand stars. And then there’s Dree, July’s green carnival, where prayers for a fertile harvest spill into laughter, apong (rice beer), and song.

These aren’t just festivals — they’re seasonal reckonings, ways of keeping the valley’s spirit in motion. As the Nyibus, or shamans, chant to appease unseen forces, you realize spirituality here isn’t something people visit on weekends. It’s how they breathe.

For the Apatanis, Donyi-Polo isn’t a doctrine so much as a compass: sun and moon as coordinates for how to live well with what lives around you. Balance isn’t abstract here—it’s practiced. Light and shade, woman and man, field and forest: each needs the other to make sense. Rivers carry wui (spirits); winds arrive with news; a grove can be a threshold. You see the faith in small, precise gestures—a farmer palming the soil before the first seed, a mother tilting the first sip of apong to the earth so the land also drinks.

New buildings rise—schoolrooms bright with posters, churches with tin roofs that catch the afternoon blaze—but the old grammar keeps threading through daily life. Priests still chant lineages that tie ridge to river; taboo groves still fence off the more-than-human; and festival days still read like contracts renewed. In Ziro, religion hasn’t hardened into ritual—it’s a relationship, tended like a field: seasonal, reciprocal, and always aware of the weather.

One morning, I met Aato Tallo, her cheeks mapped with blue lines and her nostrils adorned with round cane plugs. She laughed when I asked about the tattoos. “We made ourselves less beautiful,” she said, “so that no one could steal us.”

Centuries ago, Apatani women’s beauty made them targets for raiders. In an act of communal resistance, they tattooed their faces and wore yaping hullo — the distinctive nose plugs — to deter kidnappers. What began as protection became identity. Though the practice waned in the 1970s, the older women wear these markings like living archives — reminders that beauty, for the Apatani, was never about ornament, but agency.

In modern times, women are not just caretakers but custodians. They farm, trade, inherit land, and mediate disputes. Marriage is monogamous, kinship strong. Festivals like Myoko hinge on women’s roles as hosts and healers — their laughter is the valley’s unofficial anthem. Today, Apatani women like Yapung Tadar (an imagined name, but plausible) run eco-homestays and craft cooperatives, blending entrepreneurship with tradition.

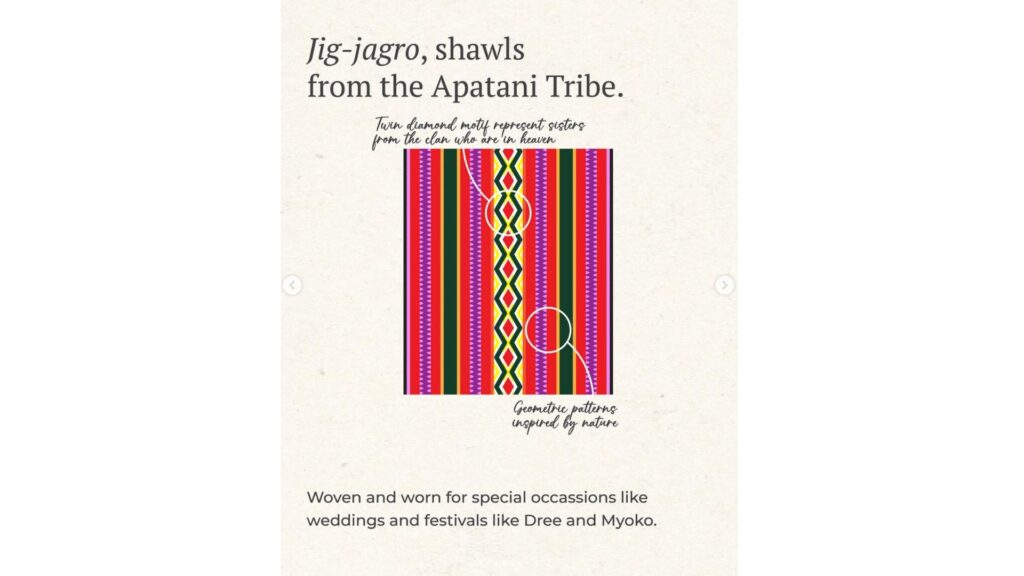

In the afternoons, you’ll find women weaving geometric dreams into cloth — triangles for fertility, diamonds for prosperity. Men carve bamboo into flutes (piim) and drums (mopi) that echo across the valley. Stories flow like rivers — myths of heroes and spirits told by firelight, always ending in laughter or song.

Meals here taste like stories — slow, smoky, and unhurried. Pork sizzles in bamboo tubes, herbs tint broths green, and pika pila, a fiery fermented bamboo shoot chutney, steals the show. Every household brews apong, rice beer so integral that refusing a cup is like skipping a handshake.

There are no wasted scraps, no excess — just a culinary philosophy of sufficiency. Even dining is communal; food, like land, belongs to everyone.

Drive into Ziro in late September and you’ll hear guitars where once only drums played. The Ziro Festival of Music has turned this quiet valley into a pilgrimage for artists — a festival where indie bands jam under open skies while Apatani hosts pour apong for strangers. Modernity has arrived here — gently. Education and tourism are reshaping lives, but not erasing roots. The youth talk of Wi-Fi and waste management in the same breath as Donyi-Polo. Progress, for them, means remembering.