In the remote Dibang and Lohit valleys of Arunachal Pradesh lives the Idu Mishmi, one of the region’s oldest tribes. Linguistic studies and oral traditions trace their migration centuries ago from the Tibetan plateau into what is now the Upper and Lower Dibang Valley, Lohit, and Anjaw districts. Over time, they adapted to the rugged environment of steep ridges, dense forests, and high passes such as Mayudia, building villages along riverbanks and mountainsides that balanced defense, access to resources, and spiritual connections to the land.

For visitors, meeting the Idu is not simply a cultural stop, it is an encounter with a community where oral history shapes identity, animistic beliefs continue to guide daily practices, and traditions remain closely tied to both ecology and ancestry.

One traveler to the Dibang Valley observed: “You walk through the forest and realize that for the Mishmi, every tree and boulder has its own biography. It makes you tread more carefully—not just with your feet, but with your mind.”

For the Idu Mishmi, the natural world is not a backdrop to human life but a community of beings with whom people coexist. Their worldview is animistic: mountains act as guardians, rivers are temperamental entities, and forests are inhabited by spirits whose moods can shape human fortune. Central to their cosmology are the creator deities Maselo-Zinu and Nani-Intaya, but the sacred extends far beyond these figures. Every stone, grove, and stream is imbued with meaning, and rituals are performed to maintain balance between the human and non-human worlds.

Ethnographers note that this worldview is not symbolic but practical. Rituals accompany key moments, including planting crops, building a new house, hunting in the forest—not simply as tradition but as necessary negotiations with unseen presences. As anthropologist Verrier Elwin once wrote of tribes in the North East, “For them the earth is not inert matter but alive, with its own will and voice.”

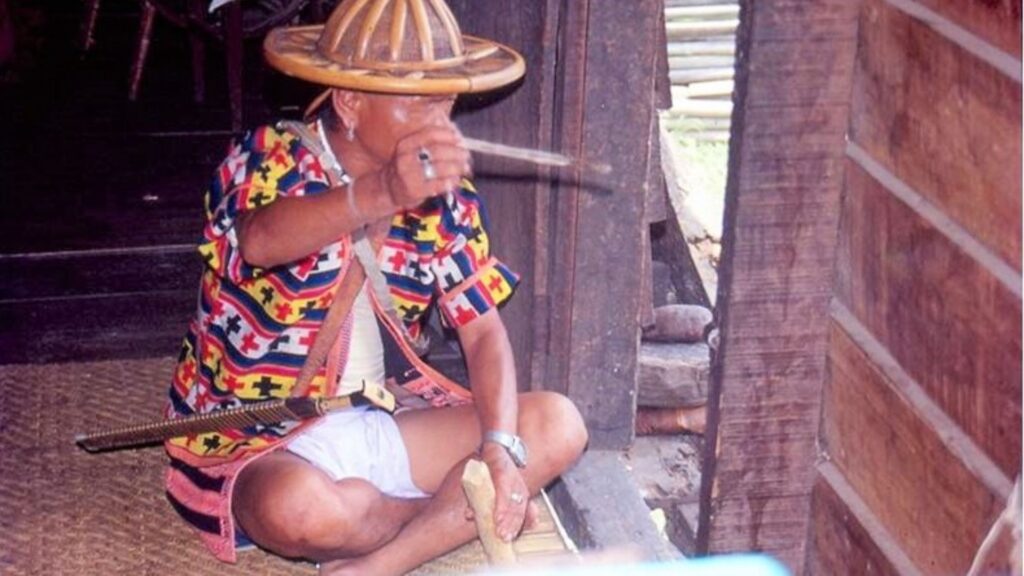

The spiritual authority of the Idu Mishmi rests with the Igu, ritual specialists who act as intermediaries between humans and the spirit realm. Their responsibilities are extensive—healing illness, conducting funerary rites, blessing new fields or houses, and addressing misfortunes believed to stem from spiritual imbalance. Anthropologists describe the Igu as “keepers of equilibrium,” maintaining harmony between human communities, the natural environment, and unseen forces. Their chants, often long mythic epics passed down orally, function as sacred texts that bind the present to ancestral memory.

Igu ceremonies can last hours or even days, involving rhythmic chanting, ritual offerings, and precisely sequenced gestures. Observers describe them as dialogues rather than performances, where the Igu negotiates with spirits on behalf of the community. One ethnographer remarked, “The Igu converses with spirits as one might with neighbors, negotiating safe passage for the living and the dead.” For travelers, attending such a ritual—always by invitation—is a profound privilege. These rites are not staged for outsiders but remain vital communal acts of balance and healing, and they demand respectful, unobtrusive observation.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Idu cosmology is their conviction that the tiger is kin, an elder brother. This belief, embedded in oral epics and ritual chants, places the tiger within the human family, shaping both moral codes and ecological practice. Unlike other animals that may be hunted for subsistence, the tiger is never pursued. Ethnographers suggest that this taboo has historically functioned as a form of conservation, ensuring the survival of a predator that shares the Idu’s forests. When a tiger is killed, whether by accident or in self-defense, the event triggers a rupture in the moral order. A multi-day atonement ceremony known as tamamma, led by an Igu, becomes necessary to appease the tiger’s spirit. Entire families and villages participate, underlining how deeply the tiger’s fate is tied to community well-being. Gender roles are visible in this ritual economy: men assist with sacrificial rites, while women prepare ritual food and maintain songs, reflecting a collective responsibility for restoring balance.

In recent years, the Idu Mishmi have been at the forefront of protests against the government’s plan to upgrade the Dibang Wildlife Sanctuary into a Tiger Reserve, arguing that such a move would curtail their access to ancestral forests and undermine traditional governance systems. Led by the Idu Mishmi Cultural and Literary Society (IMCLS), the community highlights that the sanctuary itself was declared in 1998 without proper consultation or recognition of rights under the Forest Rights Act. For the Idu, whose cultural taboos already forbid tiger hunting, state-imposed reserves are seen as redundant and disruptive. Women have played a leading role in demonstrations, emphasizing that conservation rooted in kinship—tigers as “elder brothers”—has protected wildlife for generations. As one elder explained, “We do not need guards to tell us not to kill our own brother,” capturing the tension between community-led stewardship and top-down conservation models.

To walk through these forests is to recognize that conservation is a coming together of laws, and belief systems that bind humans and non-humans into enduring kinship.

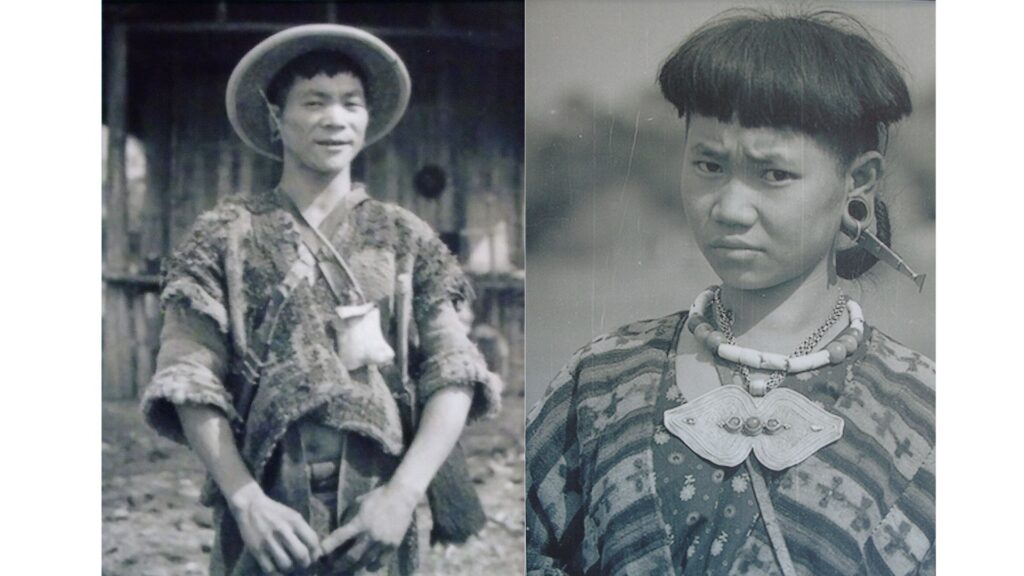

The Idu Mishmi are easily identified by their distinctive attire, which is at once practical, aesthetic, and symbolic. Woven coats, shirts, and skirts are dominated by bold contrasts of black, red, and white—colors often associated with fertility, protection, and ritual power in many Himalayan societies. The geometric patterns that cover these textiles are not simply decorative. They function as clan markers and protective symbols, encoding social belonging and spiritual safeguards against malevolent forces. Point to note is that certain motifs are restricted to particular clans or ceremonial occasions, meaning that clothing becomes a visible register of identity, age, and status.

Equally striking are the hats, crafted from plaited cane and bamboo. Everyday versions are wide-rimmed and durable, designed to withstand the persistent rains of the Mishmi Hills, while ceremonial hats are adorned with ornaments such as boar tusks, bird feathers, or beads. These additions signal rank, gender, or ritual role—worn by warriors, dancers, or ritual specialists during festivals and ceremonies. Early ethnographers like Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf observed that the Idu, like many tribes of Arunachal, used dress not only for protection against the elements but as a “portable canvas of identity,” a way of inscribing social roles onto the body. For visitors today, the attire remains one of the most immediate and vivid expressions of Idu heritage, where practicality and symbolism continue to intertwine.

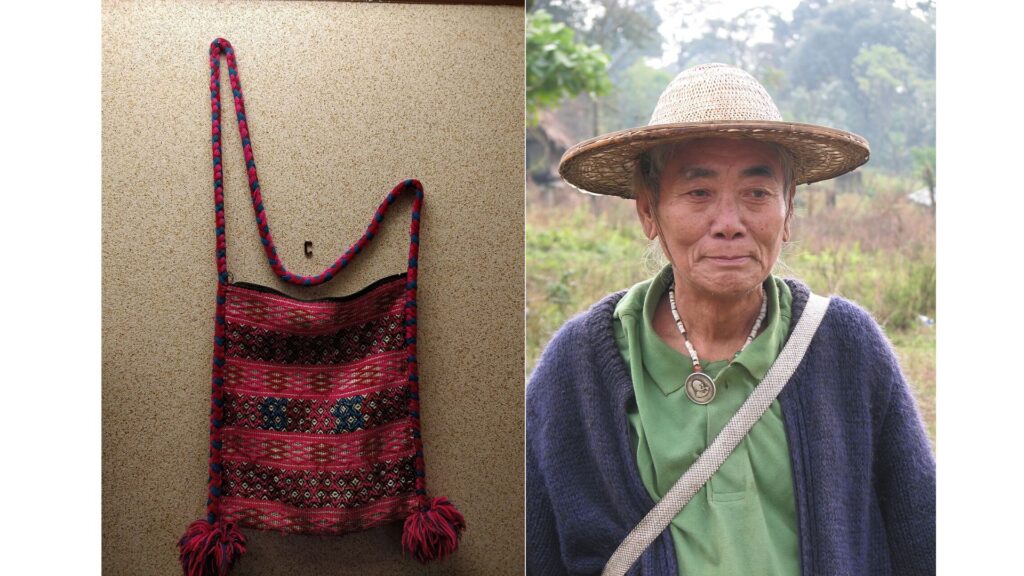

Weaving is not just craft here; it is an art form and a cultural archive. Women work on backstrap looms, producing textiles alive with motifs—diamonds, triangles, zigzags—that encode stories of ancestors, spirits, and landscapes. In 2019, Idu Mishmi textiles earned a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, formally recognizing their cultural significance and protecting them from imitation. For visitors, buying these certified textiles is more than souvenir shopping—it’s supporting artisans, sustaining heritage, and taking home a woven story.

Ask a weaver about the meaning behind her design, and you may discover that your shawl depicts mountains, flowing rivers, or mythical beings.

The Idu heartland lies along the Roing–Mayudia–Anini circuit. Begin at Roing, a gentle valley town by the Dibang River, then wind upward to Mayudia Pass at 2,655 meters for breathtaking panoramas. Continue further north to Anini, a remote settlement framed by sweeping grasslands and high ridges.

Support the weaving economy by purchasing GI-certified textiles directly from artisans. Many sellers are happy to explain the symbolism behind the designs, adding a rich story to your travel memento.

In a time when wildlife conservation often means state bans and fortress-like reserves, the Idu Mishmi remind us that there is another path: conservation through kinship. Their reverence for tigers, their animistic worldview, and their artistry in textiles offer lessons not only for anthropologists but for travelers seeking meaningful journeys.

To visit Idu land is to glimpse an ancient philosophy still thriving in the modern world. It’s an invitation to see the forest not as a resource to be consumed but as a family to be respected.

Come with permits ready, tread lightly, and compensate artisans and guides fairly. Most importantly, remember: in the Mishmi Hills, the wild is not wilderness. It is home, kin, and sacred. As a visitor, your role is not to take, but to listen, learn, and leave lighter footprints.

For a seamless, culturally infused journey—one that goes beyond sightseeing to immerse you in oral traditions, sacred geographies, and living crafts—get in touch with us. We curate travel experiences that connect you with local storytellers, weavers, and guides, ensuring your trip supports communities while giving you an authentic window into the Idu Mishmi way of life.

Why the indigenous Idu Mishmis are protesting a proposed tiger reserve in Arunachal Pradesh — The Indian Express. Access here.