Tucked away in the densely forested valleys of Arunachal Pradesh, in India’s remote northeast, the Idu Mishmi tribe lives in quiet, mystical communion with nature. While travelers are increasingly drawn to these emerald hills and cloud-veiled ridges, few grasp the spiritual world that permeates every footstep here. For the Idu Mishmis, the forest is not merely landscape—it is alive, sentient, and sacred. At the heart of their belief system lies animism, a worldview in which all elements of nature—trees, rivers, rocks, animals—are infused with spirit.

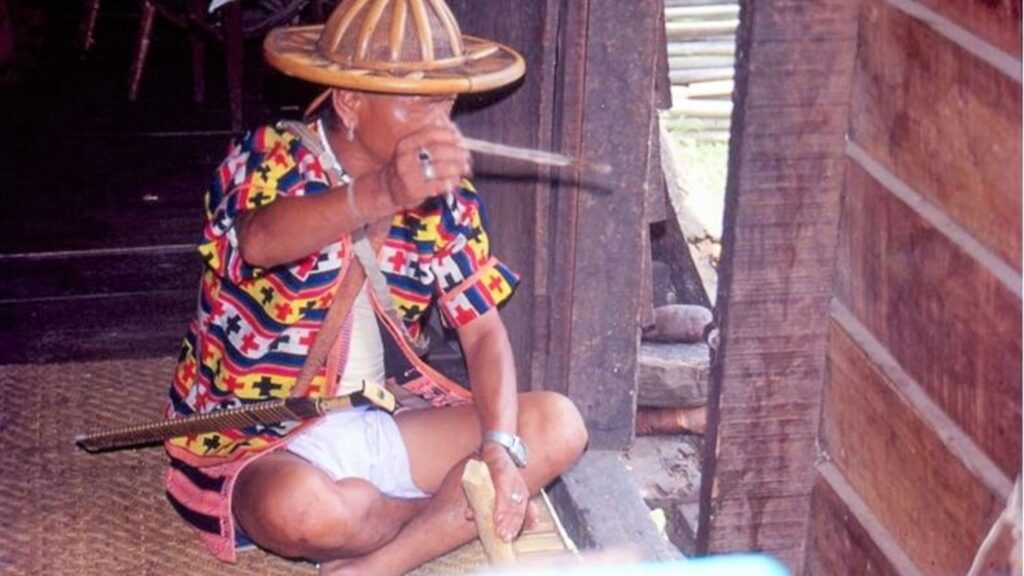

The Idu Mishmi are a Tibeto-Burman speaking tribe residing primarily in the Dibang Valley and Lower Dibang Valley districts. With a population of just over 12,000, they maintain a distinct cultural identity despite the creeping influence of modernity. The tribe is known for its intricately embroidered garments, ritual specialists called shamans or Igu, and, most notably, for their animistic spiritual practices that bind them closely to the land.

In today’s context, the Idu Mishmi are increasingly recognized for their role in forest conservation and cultural resilience, with their ecological worldview being studied as a model of indigenous environmental stewardship. Adding to their contemporary relevance is Mim Cime, the first Idu Mishmi woman to summit Mount Everest in 2018, who has become a symbol of pride and empowerment for the community.

In Idu Mishmi cosmology, nature is alive with Uyu—spiritual beings that inhabit rivers, trees, mountains, and animals. These spirits must be respected, and before any tree is felled, soil dug, or animal hunted, rituals are performed to seek permission. Shamans, often women, act as mediators between the human and spirit world, ensuring that harmony is maintained. “The forest protects us only when we respect its spirits,” shared a shaman from Anini, as noted by anthropologist Dr. Rinchin Dorje. This sacred covenant with nature isn’t just spiritual—it has functioned for generations as an indigenous conservation code.

Colonial administrators, encountering this worldview in the 19th and early 20th centuries, saw it as backward – of course! To the British, the Idu Mishmi’s refusal to extract timber or hunt freely without ritual sanction seemed like resistance to “progress.” Forests were mapped, surveyed, and assessed for commercial potential—while the tribe stood quietly, protecting sacred groves with silence and ceremony. This animistic resistance, though non-confrontational, challenged colonial logic: that nature was property, not kin. Their worldview delayed or deflected extractive projects, preserving some of the Eastern Himalayas’ last virgin forests.Even today, this sacred relationship with nature shapes how the Idu Mishmi respond to modern development. Plans for dams, highways, and mining are met not always with slogans or protests, but with ritual refusals and spiritual warnings.

For travelers visiting this lush region, it’s not just a trek through biodiversity—it’s a walk through a living temple. Understanding the forest through Idu eyes reveals not only a unique spiritual lens, but a powerful indigenous ethic that could teach the modern world what true sustainability looks like.

A unique aspect of Idu Mishmi animism is the spiritual significance given to animals. The endangered Mishmi takin (a goat-antelope hybrid), the clouded leopard, and various birds of prey are not just fauna—they are kin, ancestors, or guardians. Hunting certain animals is taboo or heavily ritualized. Killing a tiger, for instance, requires elaborate atonement ceremonies, as it is believed the tiger’s spirit could seek vengeance if not properly appeased.

This deep-seated spiritual ecology effectively functions as conservation—one that predates the notion of “sustainable development” by centuries. As such, the Idu Mishmi demonstrate how indigenous belief systems can actively safeguard natural ecosystems without formal policy or enforcement.

In the age of climate anxiety, deforestation, and biodiversity collapse, the Idu Mishmi worldview offers a refreshing, ancient counter-narrative. Their animism is not superstition; it’s a lived ethic of environmental stewardship.

Travelers, especially eco-conscious ones, can learn immensely from this culture. Spending time in Idu Mishmi villages offers more than stunning views or treks—it offers a glimpse into an alternative model of human-nature relations. With local guides, one might attend an igu ritual, walk through sacred groves, or listen to forest myths that have no written script but live vividly in oral tradition.

In recent years, researchers and conservationists have collaborated with Idu Mishmi communities to document traditional ecological knowledge and include tribal voices in forest governance. Still, the push of roads, dams, and tourism poses challenges. “The forest is changing,” said a young Idu schoolteacher in Etalin. “Even the spirits feel farther away.”

As interest in Northeast India grows, responsible travel becomes essential. Visitors must remember they are entering not just a scenic space, but a spiritual landscape. Travelers can contribute to preservation by:

“When we enter the forest, we are not alone. We walk with ancestors, spirits, and memories. The forest remembers everything.”

— Idu Mishmi oral tradition

Equal parts policy wonk and wanderlust junkie, Kavya brings together her training in environmental economics and political science with an enduring curiosity about how the world works — and how it could work better. By day, she’s a public health researcher and advocate, working at the intersection of people, systems, and the planet.

Off the clock? She’s a storyteller, active rester, and cat mama.